Japan’s Path Ahead Amid Political Uncertainty

With the LDP losing its majority, Japan has been thrown into political uncertainty. Regardless of the outcome, the country will have to confront some stark economic realities. In the short term, this should mean a large fiscal stimulus especially in the context of Japan’s tepid real wage growth.

There is currently political uncertainty in Japan, as the ruling coalition led by the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) could not secure the necessary majority of 233 seats (215 versus 279 last time) in the late October lower house election. The LDP has been in power in Japan for 60 of the last 69 years and is out of majority for the first time since 2009. An opposition coalition led by the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (CDP) could potentially muster a majority but is less likely to do so because of policy differences between oppositional parties.

A more plausible outcome is for the LDP coalition to form a minority government with support from smaller parties, including the Democratic Party for the People (DPP). In our view, the DPP’s primary contention to halve the 10% sales tax until real wages rise is neither a bad idea nor a bad bargain. Both houses of the Diet will meet on November 11 to elect a new prime minister. The current prime minister Shigeru Ishiba and the president of the CDP Yoshihiko Noda are the two candidates vying for the post as of now.

Prime minister Shigeru Ishiba was forced to walk back on his fiscal discipline rhetoric. Ishiba had floated the idea of a fiscal package matching that of the previous fiscal year as part of his election campaign. For someone who had wanted to raise taxes, this was a notable turnaround, reflecting the tough economic realities of Japan. While any new government may want to fiscally stimulate Japan’s economy, in general, governments have been fiscally responsible in recent years and this has been especially true of former prime minister Fumio Kishida (Figure 1).

Japan’s Woes

While Japan’s declining demographics and scarce labor supply have resulted in an exceptionally low unemployment rate (2.4%), wages, adjusted for inflation, have not risen as much as anticipated (Figure 2). We suspect that wages may be the key reason the ruling coalition lost its majority and why the CDP and the DPP gained 50 and 21 seats, respectively.

Based on the tough political and economic realities currently at play in Japan, inaction is not in anyone’s interest. Given this backdrop, a larger fiscal package and higher wage growth are highly likely to be pursued by any new government. This will have consequences, but they may be limited as this year’s supplementary budget will raise the fiscal bar without necessarily breaking the proverbial camel’s back.

We expect wage growth to gain more traction going forward as there is greater acceptance among businesses to more effectively passthrough costs to output prices. But more importantly, if a new government aims to keep Japan’s high government debt from growing, it needs to ensure that wages grow at a higher clip, reducing the need for supplementary budgets. We expect this year’s stimulus to be bigger than expected at around 3%-5% of the GDP. While low on probability, tax cuts are also possible, in which case policy will turn stimulative, an important tailwind for growth.

Stimulative policies are ultimately inflationary and may help to maintain Japan’s inflation at around 2%. Achieving this inflation level would mean the Bank of Japan (BoJ) could normalize policy rates to our forecast of 1% terminal rate in 2025. The BoJ, of course, will have to wade through political risks while normalizing its monetary policy, slowing the course of rate hikes. While the DPP has already called for 4% nominal wage growth next year as a precondition to raise rates, Japan's largest trade union UA Zensen has set a target 6% standard overall wage increase rate for the spring 2025 wage negotiations.

Japan’s incoming economic data is expected to highlight persistent inflation as there may be another round of hikes in output prices in the medium term. As such, housing inflation is gaining momentum, while services prices, which are more connected to wage growth impulses, may be turning a corner. Inflation dynamics have come to a phase where Japan may have to officially recognize the end of the deflation era. There are important implications to this trend. At its October meeting, the BoJ communicated that a December hike is still on the table for now, despite questions regarding its ability to enact an increase in light of recent political developments.

Investment Implications

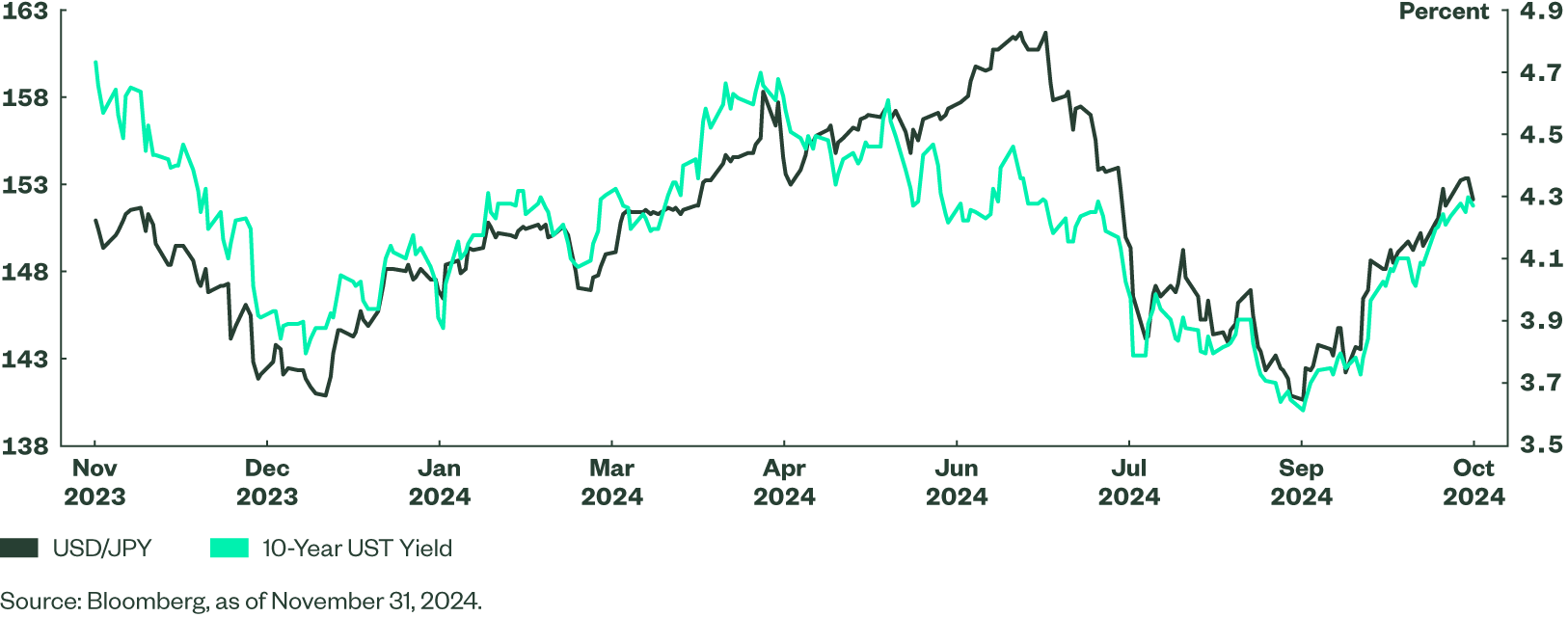

The yen is likely to take a cue from the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) next move rather than from any action from the BoJ. We anticipate this currency shift given that the declining rate differential between US Treasuries and Japanese government bonds (JGB) will continue to be a major driver for Japan’s currency (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Yen Tracks UST Yield Closely

As far as JGBs are concerned, the yield curve is expected to remain steep, with the front end remaining somewhat anchored from the gradual normalization expected out of the BoJ. However, the longer end of the yield curve is expected to edge mildly higher, pricing in higher term premium, largely attributable to easing fiscal policy.

Japanese investors who heavily invest in foreign bonds should remain invested overseas given diversification needs. Investors can expect potential capital gains from declining yields in foreign bonds versus JGBs given the rate hike possibility by the BoJ and an increase in JGB issuance. Furthermore, investors should anticipate a decline in hedging costs now that the Fed has commenced its much-awaited rate-cutting cycle.