A New Leadership Era: Institutional Meets Individual

Last year, half of humanity was placed under quarantine.i During this turbulent time, our May 2020 Global Reality Retirement Report (GR3), The New Retirement Straits, explored the impact of COVID-19 on participants’ finances — particularly on their long-term retirement outlook. In December 2020, we went back into the field for a second look at how people were faring after months of crisis. This report compares both sets of data, charting the way retirement sentiment and behavior changed over the course of the pandemic.

To level set, the biggest insight from the May 2020 data was the remarkably small impact COVID-19 and the accompanying recession made on retirement finances. Respondents reported little financial distress, and few made changes to their retirement savings — speaking to the power of default savings strategies, a stay-steady-through-the-storm investment outlook, or inertia. The survey sample composition is critical here. To qualify, respondents had to have access to a workplace-sponsored defined contribution (DC) retirement savings plan (or equivalent based on the market) and be working at least part-time. Meeting these criteria suggests a more financially secure survey population — particularly in the US, where nearly 40% of working Americans didn’t have access to a DC plan pre-pandemicii and unemployment reached historic highs in 2020. Through this lens we see a more privileged picture, but it is not perfect.

December data highlights areas where participants’ perspectives show more shades of gray.

Key Finding 1: Whether under- or overworked, employees are exhausted

Many participants reported working fewer hours and earning less pay during 2020. The youngest suffered the most and continued to bear the brunt of disruption throughout the year. In May, US workers 18-34 complained the most about reduced pay (16%) and reduced hours (27%). By December, while their pay complaints fell by nearly half to 9%, there was only a modest drop in the number who reported working fewer hours. By contrast, the same share (27%) of the next-youngest cohort (35-44) reported a loss of hours in May, but by December these older workers saw much faster improvement.

Figure 1: How has COVID-19 impacted employment?

Cutbacks were not the only cause of distress for young workers. Between May and December, those reporting an increase in hours worked doubled for those 18-34 and tripled for workers 35-44. While some may have welcomed longer hours, others may have found them an added source of strain, which over time and unchecked, could lead to a spike in burnout rates.

When asked how people were coping with pandemic-related stress, a global majority cited emotionally and physically healthy activities, with most seeking a dose of escapism (35% reported bingeing on TV and films). There was an open-ended option elected by 7% of the global sample that delivered harder truths. People cited increased alcohol consumption, comfort eating, crying, and sleeplessness; others referenced therapy and meditation. The collective sentiment expressed by these unvarnished responses signals an opportunity for greater employer engagement.

Figure 2: If you have been feeling stressed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, how have you been coping with this stress? Please select all that apply.

Key Finding #2: After austerity and isolation, participants are ready to spend

Whether Americans felt more confident about the future or simply grew tired of self-denial, by the December holiday season they had clearly decided to ramp up spending. The number who say they reduced spending on nonessential items fell from 53% in May to 47% in December. Concerningly, the number who stopped saving each month grew from 12% to 17%. At the same time, there was a 7-percentage-point leap in the number of those who increased their credit card debt — a higher jump than in the UK, Ireland, Australia, or the Netherlands. Between May and December, there was a consistent 30% slice of global respondents who said they hadn’t changed savings or spending habits.

Figure 3: What actions have you taken in response to the COVID-19 situation and its impact on your finances? Please select all that apply.

For some, spending may be motivated not only by retail therapy, but also by financial gains. In December, a larger share (29%) of American respondents said their financial picture was “better” than before COVID-19 compared to May (20%). Macro trends may have boosted their outlook. Last June, US unemployment reached a historically high 13.3%. By January 2021, the jobless rate had fallen by half to 6.1%.iii Despite the recession, few survey takers experienced a serious financial hit, and those who did saw a marked improvement by year’s end.

As the pandemic eases, sponsors have an opportunity to play a stabilizing role in reducing employee stress, as well as providing wellness and financial counseling to smooth the return to normalcy and align savings strategies with new personal wealth portraits.

Key Finding #3: Crumbling cubicle walls, work-life transparency and a definition of happiness

The pandemic brought dramatic changes to the workplace, and employees would like many of them to remain in place after the crisis is over.

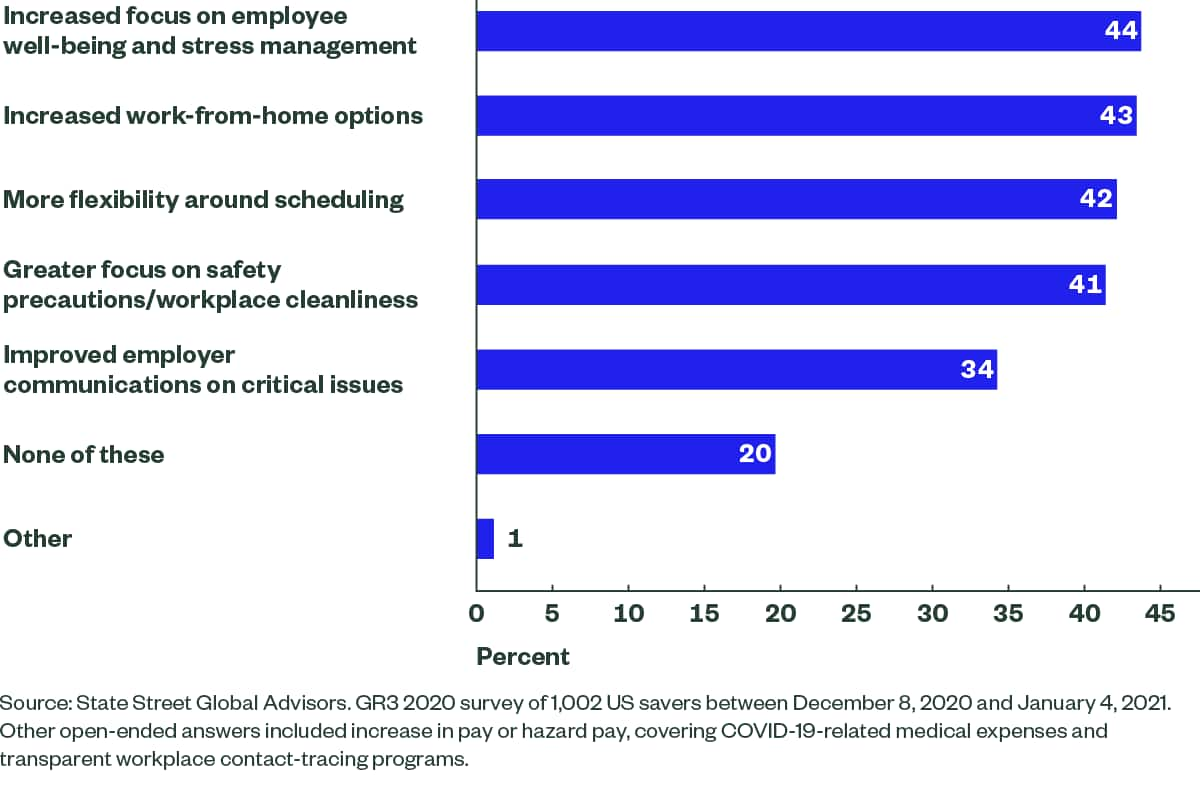

Figure 4: What new practices from the pandemic should employers adopt permanently? Please select all that apply.

For the first time, employers have seen workers in their home environments on a daily basis, struggling to calm children, control pets, and navigate interruptions with grace. As a result, companies have developed a greater appreciation for the “whole employee” and a deeper understanding of the need for social- and mental-health support.

Support from the workplace may be coming at just the right time; in keeping with the coping strategies expressed by respondents, a recent study from the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago found the number of people saying they are “very happy” reached an all-time low (14%) in 2020, and twice as many reported feeling isolated compared to two years earlier (50% vs. 23%).iv To assess how employees happiness may have affected their retirement outlook, we revisit The Happiness Formula first introduced in 2018.

The formula identifies three drivers of participant happiness:

- Trust in savings systems. A system should follow a set of understood and enforceable rules, and outcomes should be reasonably predictable.

- Ownership of retirement readiness. Workers must understand and embrace their role within the system to truly gain the value that savings structures have to offer.

- Preparedness of retirement saving and spending strategies. Preparedness points to individuals’ assessment of whether they have enough to retire.

The December GR3 data shows that two of these drivers remained strong in 2020: Americans continued contributing to their plans (“Ownership”) and also remained optimistic about their financial futures (“Preparedness”).

However, the pandemic severely eroded trust in central institutions. According to the Edelman 2020 Trust Barometer Spring Update, trust in government peaked in May 2020, then fell precipitously as Americans struggled to find reliable sources of information, supplies, support, and leadership.v Trust in all news sources fell to record lows, with traditional media seeing the largest drop. The good news: Business is now the most trusted institution, and people are looking to their employer to do the right thing — including maintaining workplace retirement savings programs. In fact, December data shows 57% of survey takers disagreed with the idea of sponsors suspending or reducing retirement plan programs as a COVID-19 crisis management tactic, up from 50% in May.

Key Finding #4: Distrust is casting a shadow on retirement readiness confidence

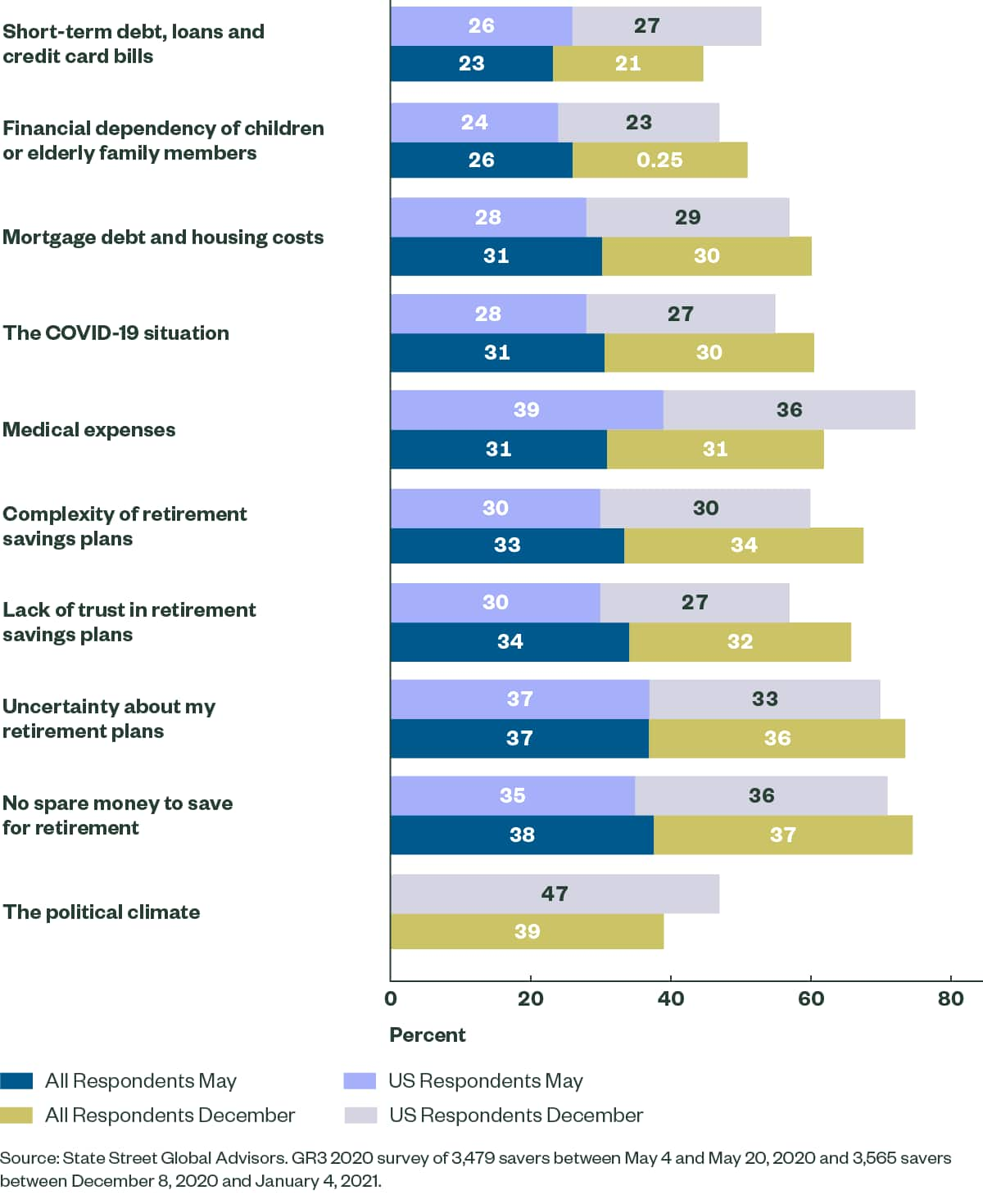

In assessing respondents’ greatest retirement-security fears in December, the political climate, an option added to the December survey, surpassed nearly all others globally (47% in the US, 40% in Ireland, 39% in the Netherlands, 37% in the UK, and 33% in Australia, where the concern had a middling rank). In the US, this concern highlights the upheaval following the 2020 presidential election (the January 6, 2021 attack on the US Capitol took place days after the survey closed) and is meaningful in its eclipse of medical-expense fears. In fact, American’s concern that medical expenses could erode their retirement savings dipped slightly from May to December, potentially suggesting a lessening of COVID-19 anxieties, though health-care costs — and by extension the health-care system — remain a top-three issue for Americans.

Figure 5: To what extent do the following negatively impact your confidence levels around being financially prepared for retirement?

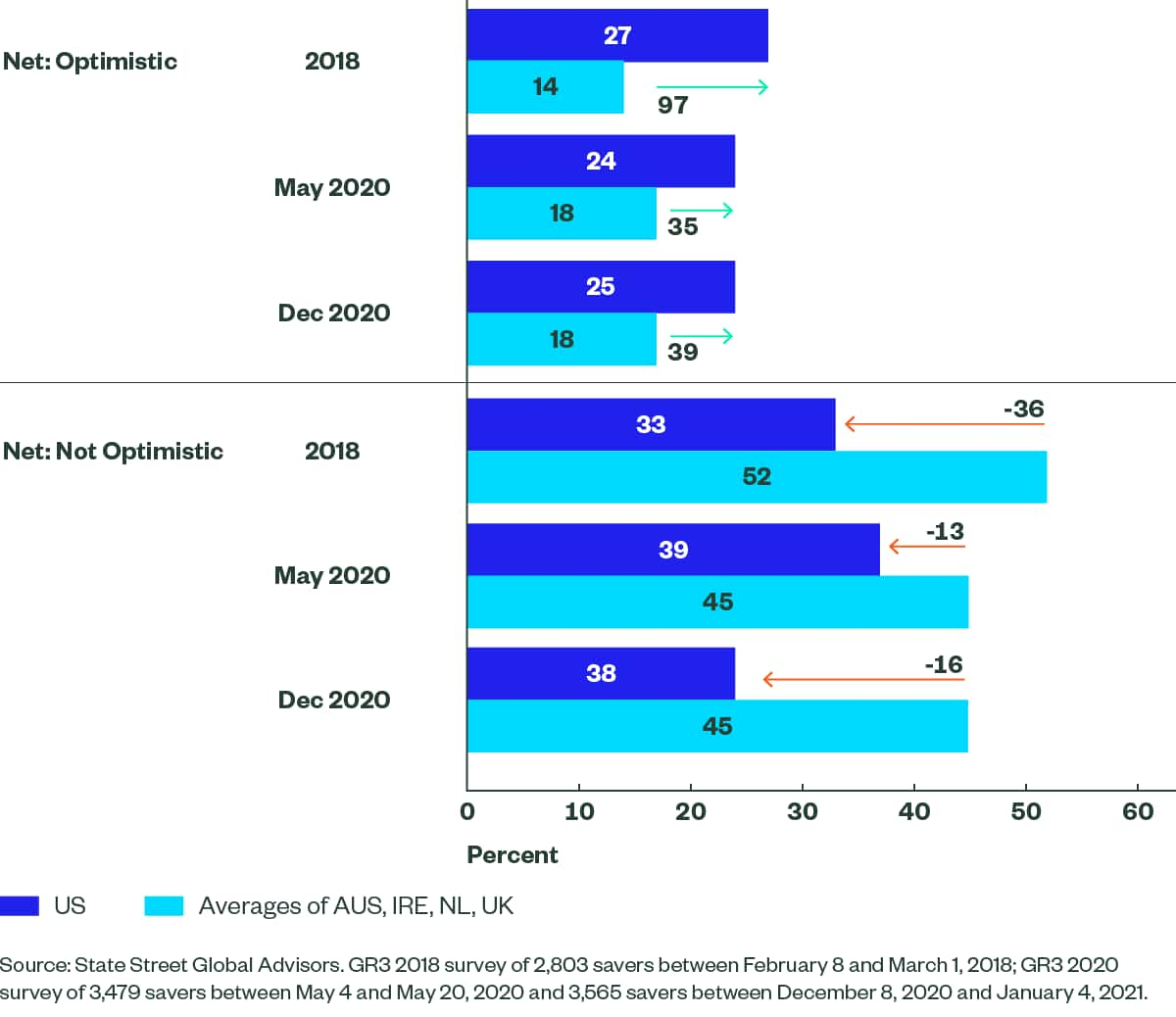

Key Finding #5: Retirement optimism and plans remain steady

Optimism levels scarcely budged between May (24% “optimistic”) and December (25%), as have people’s plans for retirement. Half (52%) of global survey takers over age 55 haven’t changed retirement plans, and an additional 22% have no existing plans to change. Of the remaining 26%, most planned to defer retirement, while the lesser portion who planned to retire early cited varying reasons, including a change in priorities, extended unemployment, or — at the other end of the spectrum — financial ability.

For those global respondents age 54 and younger, 64% have not considered retiring earlier than planned in light of the pandemic, and another 22% have not considered the matter. For the 14% who have, their driving motivation was that their view on life had changed, followed by managing the impact of the pandemic on their family. Arguably, these motivations could be linked.

The practical element of retirement planning — saving — saw some change in response to COVID-19, with about 30% of respondents in the UK, Ireland, and Australia saving more by December 2020. In the US, however, Americans mostly held steady, an overall survey theme. Americans’ opinion of investment risk also remained unchanged. The percentage of those who preferred retirement investments with a high risk-reward profile barely nudged downward from 24% in May to 22% in December, suggesting plan participants saw no reason why short-term market volatility should affect their long-term retirement investments.

The fixed lens of optimism is best highlighted by Figure 6, as the US continues to have the most sanguine view of the future, one that has incrementally improved from May to December 2020 as the world inched closer to approved COVID-19 vaccines and decreasing rates of infection. Despite the sleepless nights, Americans are anticipating better days.

Figure 6: How optimistic are you that you will be financially prepared for retirement by the time you stop working?

A new way forward, led by institutions mirroring individual values

While the pandemic left most employed savers on track to meet their financial goals, the crisis altered the collective perspective of the global workforce. The lessons of humanity, responsibility and flexibility gained from the pandemic will be central to both an evolved experience of work and redefined employer-employee relationship. By embracing these values, employers have the opportunity to make a meaningful impact on employee engagement generally and retirement outcomes specifically. Here’s to a new definition of happiness.

What employers can do:

- Speak truth with empathy, earning trust through reliability and relatability.

- Introduce retirement income plan options that build on established trust and boost employees’ confidence in their future security.

- Adopt a “whole employee” approach that addresses the full spectrum of pressures workers face with flexible, well-coordinated personal and financial wellness programs.

- Take a broader stance through advocacy for public policies aimed at strengthening the pillars of the retirement system.

Survey methodology

Following the frenzy of the peaking pandemic in spring of 2020, State Street Global Advisors commissioned global analytics firm YouGov to conduct an online survey across five countries in December 2020 to monitor any change in sentiment over the course of the year. YouGov surveyed 3,565 individual savers with access to defined contribution schemes between December 8, 2020 and January 4, 2021.

| Region | Number Surveyed |

|---|---|

| Australia | 543 |

| Ireland | 506 |

| Netherlands | 505 |

| United Kingdom | 1,009 |

| United States | 1,002 |