German Election: “Alternative zur Stagnation?”

The German federal election moved to 23 February following the collapse of its governing coalition in December.

The upcoming election is less of a global macro event than previous election cycles, mainly due to the narrow range of German policy outcomes, and global policy drivers – even the ones relevant for Germany and Europe – are found more in the United States (US) and China.

The election arithmetic suggests a centrist coalition with a limited mandate. This means, barring a post-election surprise – policy reversal by one of Germany’s main parties – existing macro and market trends are likely to continue in the near term. These include economic weakness, declining rates, and a weaker euro.

Intra-eurozone bond spreads could narrow (except in France) as Germany embarks on a modest fiscal easing, while the periphery should continue to outperform economically. The exception could be equity performance as German corporates adapt to changing global market conditions even as the home market stagnates. The risk here is from weaker global demand based on US trade policy and China’s domestic economy.

Election Dynamics Only Allow for a Modest Policy Shift

The reality of Germany’s electoral system has now produced limited arithmetic combinations of viable coalition governments. The prominence of parties such as the Left Party or Alternative for Deutschland (AfD), viewed as extreme by the mainstream, have reduced the possibilities for governing. This year the AfD is polling in second place, hovering around 20% of the vote.

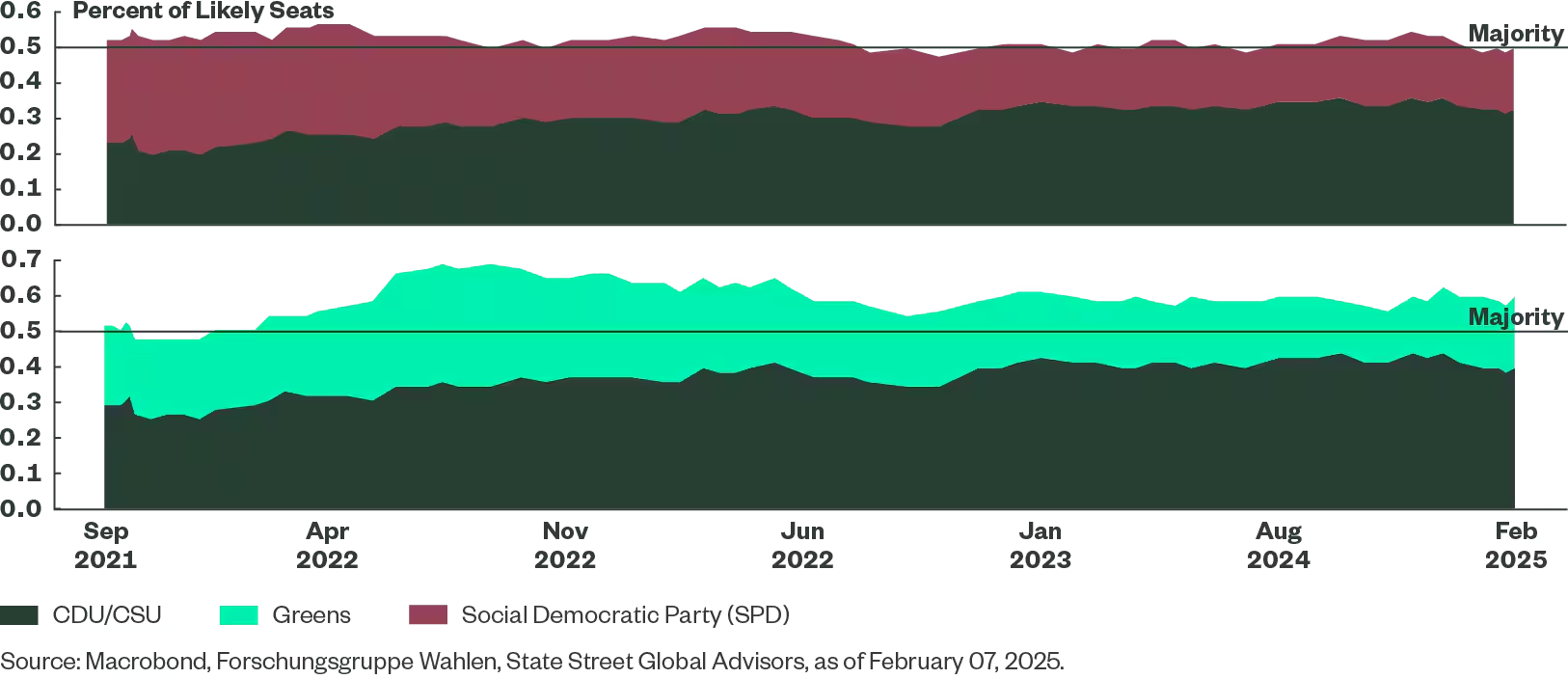

This means the residual seats up for grabs are fewer and it is harder to reach a majority in parliament with only two parties. Figure 1 shows our estimates of national polling as applied to parliamentary seat wins, with both the Christian Democratic Union (CDU)/Christian Social Union (CSU)-Social Democratic Party (SPD) as well as the CDU/CSU-Greens coalition teetering around a narrow majority.

Figure 1: CDU/CSU Led Coalitions With SPD and Greens

Either coalition would be limited in terms of policy swings given the gaps between the center-right CDU/CSU and the other two coalition parties. The worst outcome for policy would be if neither of these coalitions gather enough for a majority and are therefore forced into a three-party coalition, further limiting policy initiatives.

Germany in Need of Investments

The past five years have been modern Germany’s worst in terms of economic performance, outside of the world wars. The reasons are well known – a fundamental loss of competitiveness due to repricing of energy costs, the rise of Chinese industrial competition in core German sectors, and a chronic shortfall in domestic demand. While unemployment has only just begun to tick up and is still at a historical low of 6.2%, corporate insolvencies have skyrocketed to the highest level since the 2008 financial crisis (Figure 2).

Typically, the macroeconomic adjustment would be a revival of export growth, especially on the back of a weaker currency, but China has displaced German imports in its domestic market. Other emerging markets remain tepid, and fears of US protectionism keep investment in the export sector at bay.

It’s All About Fiscal Priorities

European elites have flagged the required medicine to relaunch economic growth. This includes a substantial boost to public investment in underfunded infrastructure, wide-scale de-regulation, and incentives to finance more risk-taking across the economy. In this regard, the recent Draghi report particularly applies to Germany in its calls to raise investment, promote innovation, and reform competition.

The problem is that German politicians have been unable to embrace the necessary changes. The current election campaign has at least debated the need to reform the constitutional debt brake that limits structural fiscal deficits to 0.35% of GDP, but there is still no clear majority for wholesale reform. The center-left parties have called for reform and the creation of a public investment fund outside the debt limit, while the center-right parties are only countenancing minor tweaks to extra-budgetary financing. In short, it is hard to imagine a big shift on the most central issue of this election, namely Germany’s fiscal stance.

The irony is that one of Germany’s remaining big competitive advantages is the country’s fiscal space. At 62% of GDP, the public debt ratio is considerably lower than that of other large, developed economies. Given that Germany can fund itself at an average rate of less than 2.5%, it would be easy to identify public spending that generates greater returns. Any public investment is also likely to lift the country’s productivity rate and therefore should be fiscally positive in the long run.

The harder policy challenges revolve around how to contend with major external challenges such as Chinese competition, US protectionism, and rising security costs. And internal challenges include finding novel approaches to foster the energy transition while preserving competitiveness, digitizing the economy, creating new sources of innovation, and balancing aging demographics with the social problems emanating from excess immigration. In this context, higher public investment should be an achievable goal, but we only expect a headline fiscal boost of less than 1% of GDP by 2026.

Investment Implications

Germany’s modest fiscal expansion will not be enough to change the investment fundamentals for German and European assets. Weak economic growth, albeit stronger than in 2024, coupled with falling inflation will keep bond yields in decline and the euro weak in the near term. However, greater issuance of Bunds and the growth gap in favor of Europe’s periphery imply narrower spreads between Bunds and peripheral bonds. The exception is France where we continue to see political paralysis and fiscal excess weighing on long-term government bonds (OATs).

German equities have performed well recently, and the next government is likely to be more business friendly, sparking off some modest animal spirits. But German companies remain vulnerable to global growth trends – this means, less US protectionism and stronger Chinese stimulus than expected would be an important tailwind for equities.