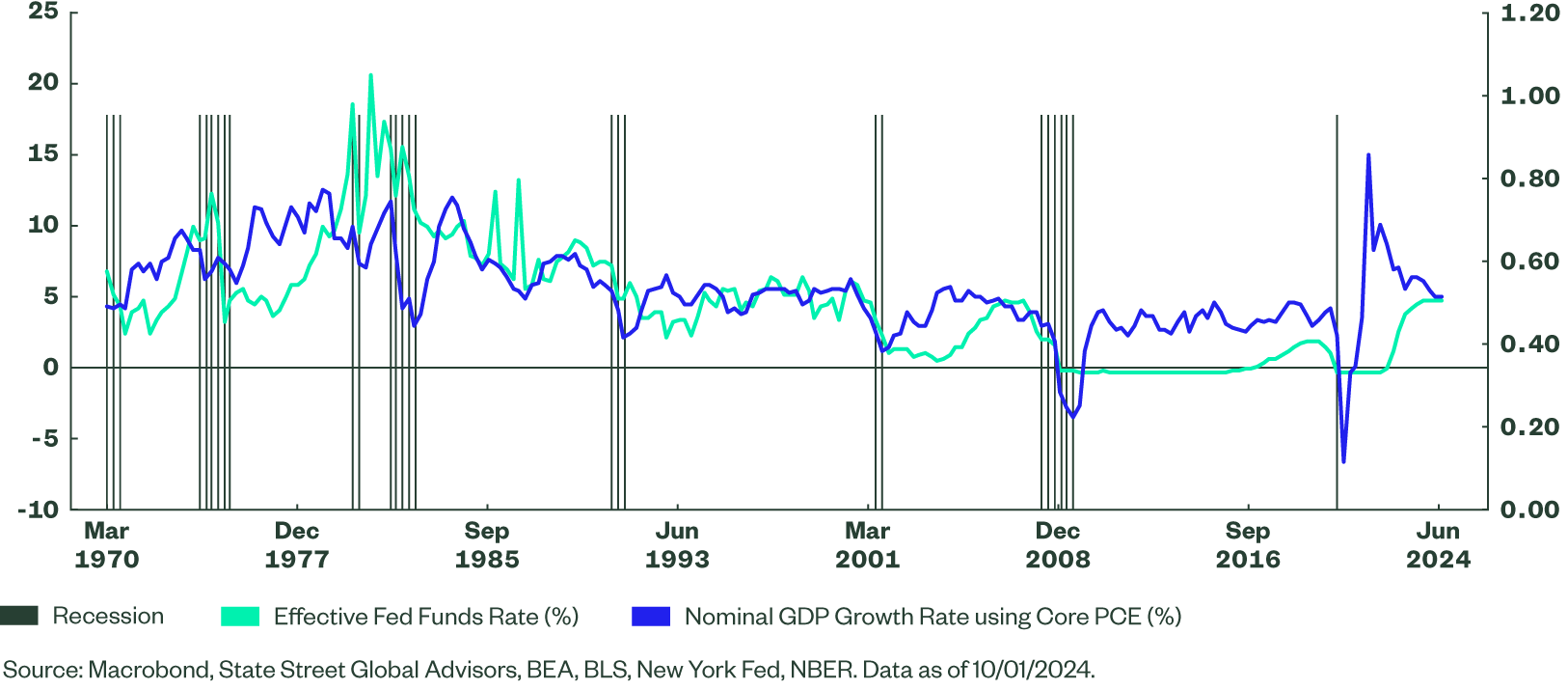

When Policy Rates Are Higher Than Growth

Historically, every recession since the 1970s has been preceded by or coincided with the Fed keeping rates above nominal growth, creating tough economic conditions. With inflation moderating and growth stabilizing, the Fed’s interest rate is nearing GDP growth, indicating a potential shift toward a more favorable outlook.

For the September FOMC meeting, the consensus among economists was for a 25 bps cut, but the market was pricing in a steeper 50 bps cut. In the end, the market consensus predicted correctly. Moreover, the decision to cut by 50 bps versus the usual 25 bps was not unanimous, with Michelle Bowman becoming the first governor since 2005 to cast a dissenting vote in favor of a 25 bps cut. Chair Jerome Powell rationalized the decision by citing the continued progress on inflation while also acknowledging the softening labor market conditions. While the decision was largely viewed as an effort by the Fed to preserve the soft landing, concerns remain that the Fed is “behind the curve” and may have kept policy tight for too long.

In that regard, it is worth examining the historical evidence by looking at the relationship between the Fed funds rate and nominal growth, calculated as Real GDP Growth Rate (%) + Core PCE (%). As shown in the chart above, all recessions since the 1970s have either been preceded by or coincided with the Fed raising or holding interest rates above the nominal growth rate. Essentially, interest rates that are higher than the growth rate have proven to create a difficult environment. Put differently, barring the 1990s, continued economic expansion has required the Fed funds rate to be below the nominal growth rate. Currently, with inflation moderating and growth returning to trend, the Fed funds rate is just now approaching GDP growth. Considering the Fed has already cut by 50 bps with more rate cuts to follow, coupled with the fact that the Atlanta Fed nowcast is pointing toward solid GDP growth in Q3 (>5% in nominal terms), conditions for a soft landing appear to be well in place, and rates may remain below growth.

However, downside risks to the growth outlook persist in the form of a softening labor market, a weak manufacturing sector, and turbulence in China, particularly if recent stimulative measures aren’t enough. Any further deterioration in the employment front could hurt consumption and require the Fed to step up policy support. The Fed shifting its focus to the employment part of its dual mandate is a step in the right direction to preserve the soft landing. Please refer our latest Global Macro Policy Quarterly update for our updated economic views and forecasts.