Casting a Wide Net: Why True Passive Strategies Are Rare Catches

With the rapid expansion of index funds, including smart beta and factor portfolios, investors are able to cast a much wider net when selecting the strategies that best meet their goals and risk tolerances. However, what is active versus what is passive has become difficult to discern.

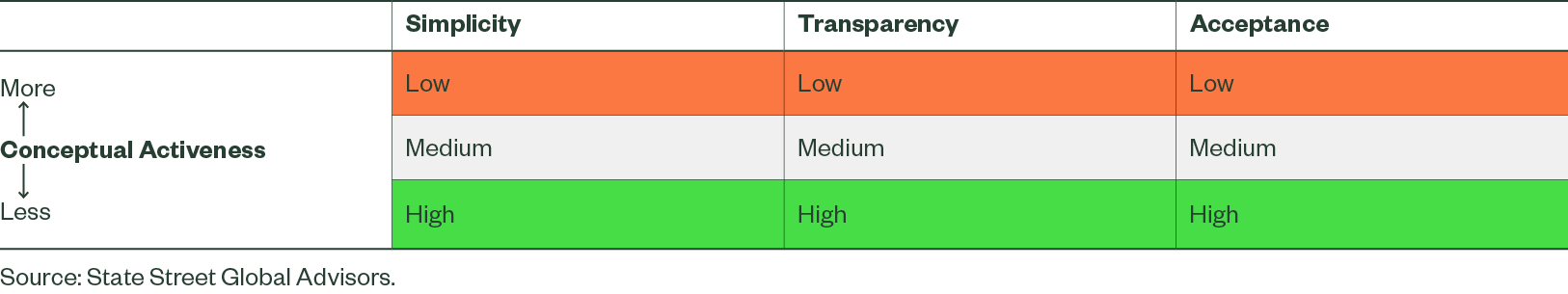

In our view, everything that is active lies on a spectrum and can be evaluated based on a framework we call “conceptual activeness.” We discuss three key parts of conceptual activeness—simplicity, transparency, and acceptance.

A version of this paper has been accepted to The Journal of Beta Investment Strategies for its Winter 2024 Issue.

The Shifting Boundaries Between Active and Passive Investing

As investors weigh the growing pool of options for assets that could meet their investment goals, it is worth considering how to apply active versus passive designations. In this piece, we discuss the following data-driven observations about where various asset classes fall on the active management spectrum.

- The only truly passive investment strategies are broad market-capitalization weighted index portfolios. Every other investment strategy, including smart beta, is active. We propose a framework—conceptual activeness—to capture the continuum of active strategies.

- Activeness is not one dimensional. We set out three additional dimensions that inform the degree of activeness of a strategy—simplicity, transparency, and acceptance (STA). Strategies can rate as low, medium, or high on any of these three dimensions, so the degree of activeness is multidimensional.

- Systematic strategy design decisions (including identifying and defining the objective, the alpha signals or factors, the portfolio construction approach, and the implementation) all inform the strategy’s STA characteristics.

Conceptual Activeness: A Framework For Making Sense Of The Active Spectrum

We have long believed that activeness is not one-dimensional. The most commonly used metrics are ones that typically focus on how much the strategy deviates from the benchmark, such as active risk (tracking error) and active share. Although this is useful for understanding the amount of benchmark relative risk an active manager is taking, it is not as useful for understanding how other approaches on the active-passive continuum, such as smart beta, fit in. Smart beta strategies, for instance, can be designed to have relatively large amounts of active risk or active share.

To make sense of how smart beta, factor investing, and other index strategies (which we have already determined not to be passive) fit in the spectrum, we turn to an idea we call “conceptual activeness.” The conceptual activeness (CA) of any strategy can be evaluated along three dimensions:

- Simplicity (S): the strategy design decisions are relatively simple and intuitive (the more simple = the less active)

- Transparency (T): the level of transparency available to different market participants (the more transparent = the less active)

- Acceptance (A): broad acceptance across the ecosystem of market participants (the more acceptance = the less active)

Passive-adjacent index portfolios (the closest we can approximate the TMP) have the highest level of simplicity, transparency, and acceptance (STAs). (It’s helpful to note that these characteristics result in the practical attributes of low cost, low turnover, high liquidity, and high capacity. These practical attributes are not independent of the STA framework.)

Understanding a strategy’s STA profile allows us to place it on the active-passive spectrum. How far a strategy deviates from passive along this STA scale, and along which dimensions, helps us identify the degree of activeness of any strategy. It is important to note that a strategy can be less active in one dimension and more active in other. (We provide an illustration later with the Size factor.) Figure 1 provides a visualization of the STA framework.

Figure 1: Illustrating Conceptual Activeness: A Framework for Measuring Activeness

The more often a strategy is “high” in the three dimensions, the lower its conceptual activeness. Conversely, the more often a strategy is “low,” the more active it is. But how do we assess simplicity, transparency, and acceptance? What are the overarching principles, design components and decision factors influencing a strategy’s relative simplicity, transparency, and acceptance levels?

The simplicity principle: This pillar, perhaps, suffers from the most amount of subjectivity; what is simple for a quantitative investor of two decades, may not be simple for an amateur stock picker. Simplicity could refer to the choice of portfolio construction approach (rules/based tilted versus optimized), the number of factors chosen (few versus many), the extent of intellectual property reliance (versus publicly available or third-party data sources), or the amount of deviation from the traditional mean-variance optimization framework. The lower the simplicity, the higher the conceptual activeness.

The transparency principle: There can be several levels of transparency in strategy design—what is transparent to the public (e.g., through information contained in offer documents or fund factsheets), what is transparent to the investor (e.g., in 1:1 communications), and what is only transparent to the internal investment team. Transparency can also manifest differently across components of the strategy. Although factor metrics might be transparent to the investor, the specific modelling choices (e.g., normalization procedures and data treatments) may not. The lower the transparency, the higher the conceptual activeness.

The acceptance principle: Acceptance can also be evaluated in a number of different ways—for example, that which is broadly cited in academia or practitioner thought leadership, or where there is widespread industry acceptance viewed through commercial indices and products. Acceptance can be measured across areas such as portfolio construction approach standardization; the pace of innovation (a high pace is unlikely to be broadly accepted); factor decay risk (a signal anchored on mispricing is unlikely to be broadly accepted given the risk of excess returns being arbitraged away); as well as the level of skill required (the more sophisticated the model, the less likely it can be broadly understood and therefore accepted). The lower the acceptance, the higher the conceptual activeness.

There are two important points to note. First, conceptual activeness is independent of active risk. Consider, for instance, two strategies offered by a manager that are simply calibrated at different risk levels. If both use the same intellectual property, data inputs, and portfolio construction tools, but one targets 3% active risk and the other 7% active risk, they still have the same STA profile. Moreover, the STA profile measurement should always be relative to the passive-adjacent portfolio, thus meaningfully reducing subjectivity.

Find Out More by Downloading the Full Research Report

Our peer-reviewed research paper gives our full thinking about what we consider active versus passive, including historical context—i.e., how active and passive management have both evolved over the past half century. Furthermore, we unpack why investors and index creators may have different perspectives on active versus passive, as compared with investment strategists. Finally, we explain how to link strategy design to conceptual activeness, and we provide a case study on how conceptual activeness can be applied in practice.