European Parliament Elections Matter in the Medium Term

The European Parliament elections, occurring between June 6 - 9, are among the largest and most complex in the world, spanning 27 countries and over 370 million potential voters. Despite their scale, the elections are not a significant market event. However, we do see emerging themes that are net negative for the bloc in the medium term by stalling further integration and improved fiscal coordination across the region.

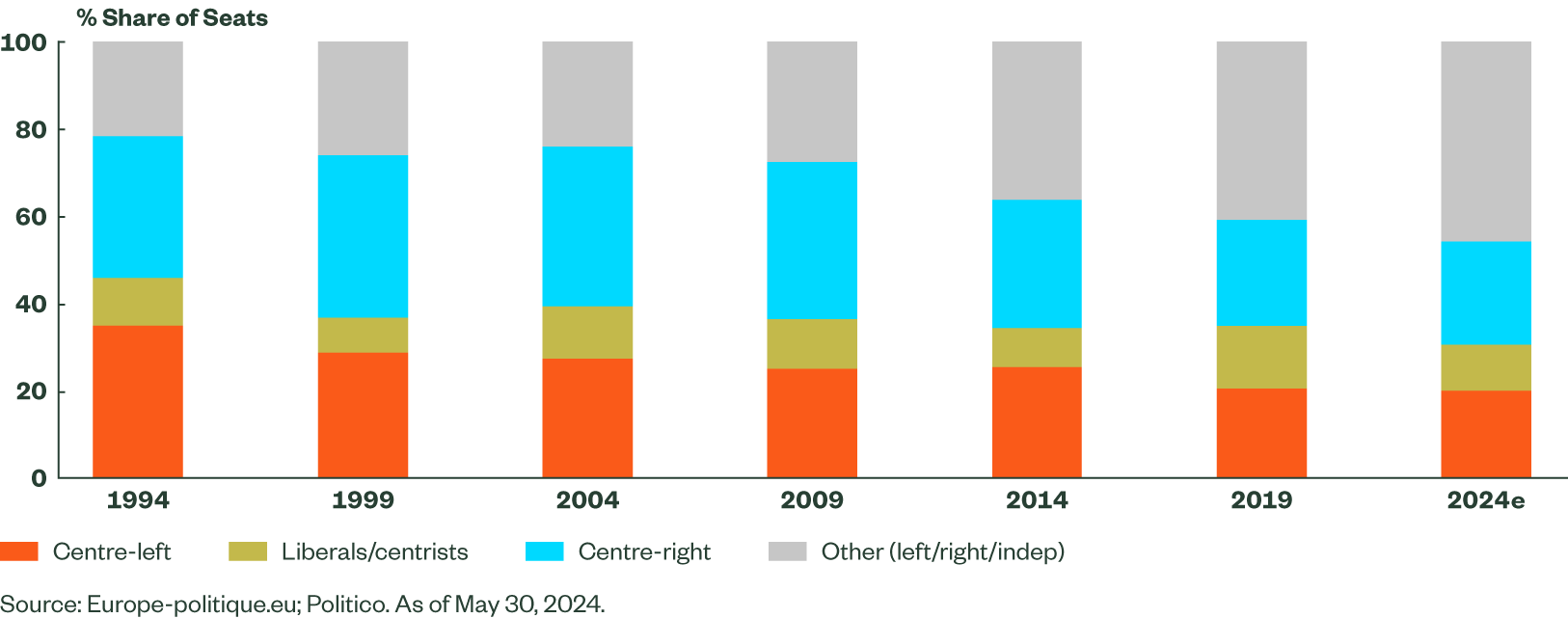

Since direct elections to the European Parliament began in 1979, it has been dominated by a loose centrist coalition: the centre-left Socialists and Democrats (S&D) and the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP). The two had historically held 50-to-70 percent of seats between them, but this has been changing in recent years as right-wing Eurosceptic parties have made greater inroads.

The upcoming elections are expected to maintain the rightward shift. Polls expect the two dominant parties to emerge with just over 40% of seats between them, a historic low. This result will ensure that centrist voices continue to control the debate, but it will make it harder to ignore voices from the right. Indeed, explicit overtures to the right by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen may undermine her bid for re-election, although that is still the most likely outcome.

Figure 1: Non-Centrist Voices, Mainly on the Right, Are Growing in the European Parliament

As noted, the elections themselves are not a market event. If elections to national parliaments can feel remote, the European Parliament is even further removed. This is by design. For one, it shares legislative power with the European Council.1 However, there are other weaknesses as well, including a lack of discipline within the groupings (i.e., parties) due to the wide political spectrum and different national priorities. If shifting political winds define national parliaments, it can be said that a gradual change in temperature is what defines the European Parliament.

But investors should not ignore the elections’ results. An increased number of right-wing voices will shift European Union (EU) policy in that direction as politics are to a greater extent driven by issues rather than parties (as is normally the case national parliaments). This shift matters for member states, given the pre-eminence of EU law over domestic legislation. It also matters internationally as it defines where the EU sits on global issues — from its own competitiveness to matters of trade and security.

Shift to the Right Has Already Begun

Some new themes are clear. The right has some common policy preferences including: distrust of European authority, scepticism over global issues, and greater demands around security. Accordingly, we expect the EU agenda to become less ambitious on the green transition, social justice, and projects such as a common capital market. It will likely be more protectionist on migration and trade and more ambitious on defense. Indeed, the shift has already started; the EU was surprisingly quick to water down its climate agenda when farmers protested early in 2024.

Seen from a geopolitical perspective, this shift is a step backwards. Some of the challenges Europe faces today are geopolitical in nature – global competitiveness, climate change, external security. In a world increasingly defined by national interest than global rules, Europe’s biggest asset is its size. To wield it effectively, Europe itself needs to evolve to be more state-like, with common debt, a common fiscal policy, a common capital market, and common defense. A rightward shift in policy makes achieving any of these more difficult, even if the magnitude of the shift is modest.

The Bottom Line

We see the elections as a moderate headwind for the EU. Polls indicate greater far-right representation in the new parliament term, which, all else being equal, will make it more challenging for the EU to navigate the new geopolitical landscape. As this touches upon fundamental questions of EU competitiveness, we see the elections as modestly net negative for European assets in the medium term.