Early Bird Gets The Worm The Opportunity Cost Of Higher Rates In Australia

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) made a soft pivot in their policy stance in September, as they did not explicitly consider a rate hike for the first time in almost a year. The market did not take much notice of this subtle shift, and for good reason, as the overall stance remained hawkish and in line with Governor Bullock’s August guidance that interest rates would not be cut this year. These developments solidified the consensus for February 2025 as the timing for the first rate cut. Regular readers know our dovish concerns in Australia; in this piece we layout why it is important for the RBA to recalibrate rates lower and what could be the consequences of a further delay.

Our primary contention against the consensus pricing of the first rate cut is that it is almost two full quarters from now. In this period, economic momentum could falter more than the 0.2% q/q growth rate in Q2, which translated into the lowest annual growth rate in three decades. We worry that this could be the cost of the higher-for-longer-than-necessary policy stance. The key arguments for and against lower rates in Australia are listed below, and we see a clear case for lower rates.

Table 1: There Is A Clear Case For Lower Rates In Australia

| Arguments for higher for longer | Arguments for lower rates |

| Core CPI remains higher than headline | Leading indicators: lower inflation Discretionary inflation* was 2.1% in Q2 |

| Labor market remains strong | Leading indicators: higher unemployment 77% jobs created since 2023 in just 4 industries |

| The level of demand is still above supply | GDP growth lowest in 32-years Consumption growth lowest since 15-years |

# as answered by Governor Michele Bullock during the press-conference in September

*excluding tobacco. Source: SSGA Economics, ABS

Australia vs the US

Although all central banks primarily respond to developments in their domestic economies, global cycles have an impact. In that regard, there are plenty of similarities between the US and Australia. First, and most importantly, inflation is clearly declining, but the lack of (complete) monthly CPI data in Australia paints an incomplete picture that lowers conviction in the view. Furthermore, consumer sentiment has been trending weak in both countries. Finally, the labour markets are strong, with Australia’s marginally better. Unemployment rates in the two countries were exactly the same1 in August. Yet, the US Fed delivered a proactive cut of 50-bps to conserve the labour market’s strength, while the RBA still sees the labour market as a potential threat to ongoing disinflation.

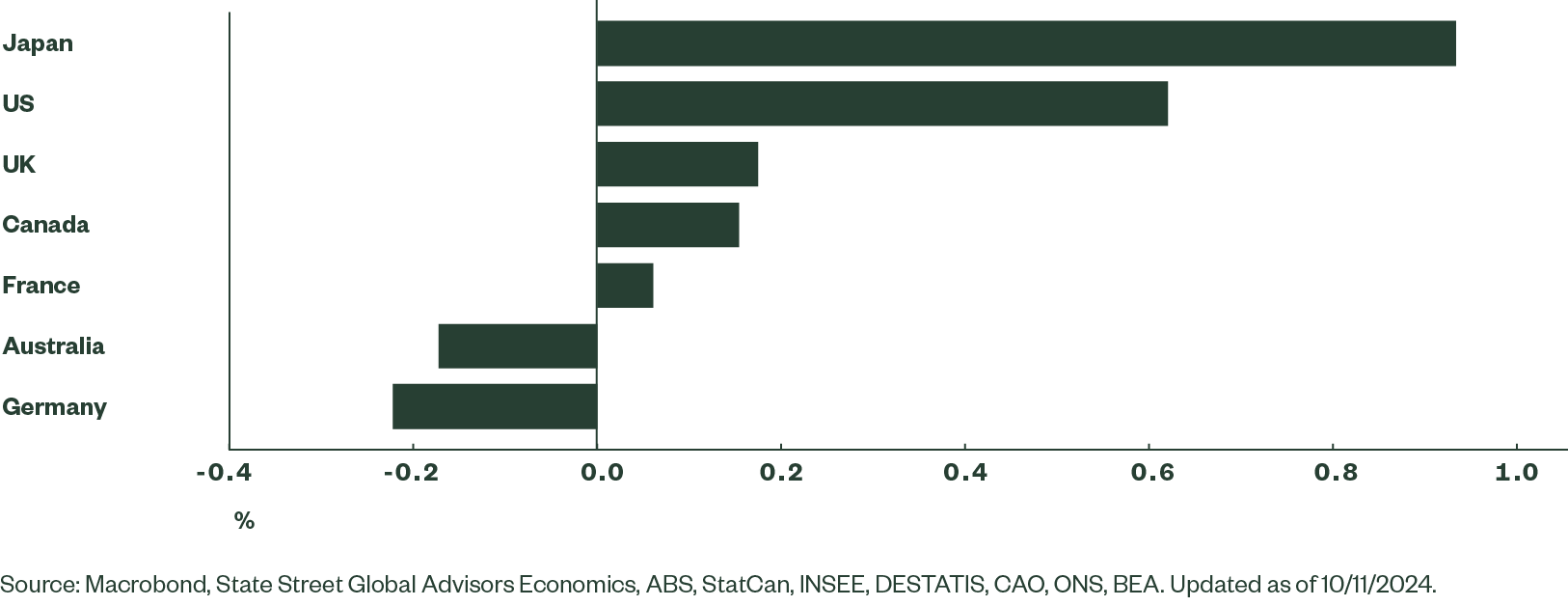

The key difference is economic growth; GDP growth in the US is still tracking at 3.2% for Q3 according to the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow Tracker, while that in Australia was the weakest in three decades in Q2. Further highlighting this divergence, Australian consumption declined in Q2 and was the weakest among advanced economies after Germany, something that has happened very rarely in Australia’s history.

Figure 1: Household Consumption in Q2 2024

This data provides a sneak-peak into how bad growth could be if rate cuts are delayed. It also goes a long way to show how restrictive monetary policy is in Australia. Consequently, our worries on growth worsened; the Westpac-Melbourne Institute (MI) Leading Index dropped to an eight month low in September and is implying that sub-par growth could continue ‘in the first half of 2025’ (source). We recently (source) downgraded Australia’s 2025 GDP growth to 2.0% from 2.6% for these reasons.

Figure 2: Aussie Economy’s Weak Growth Outlook

Inflation and the labour market

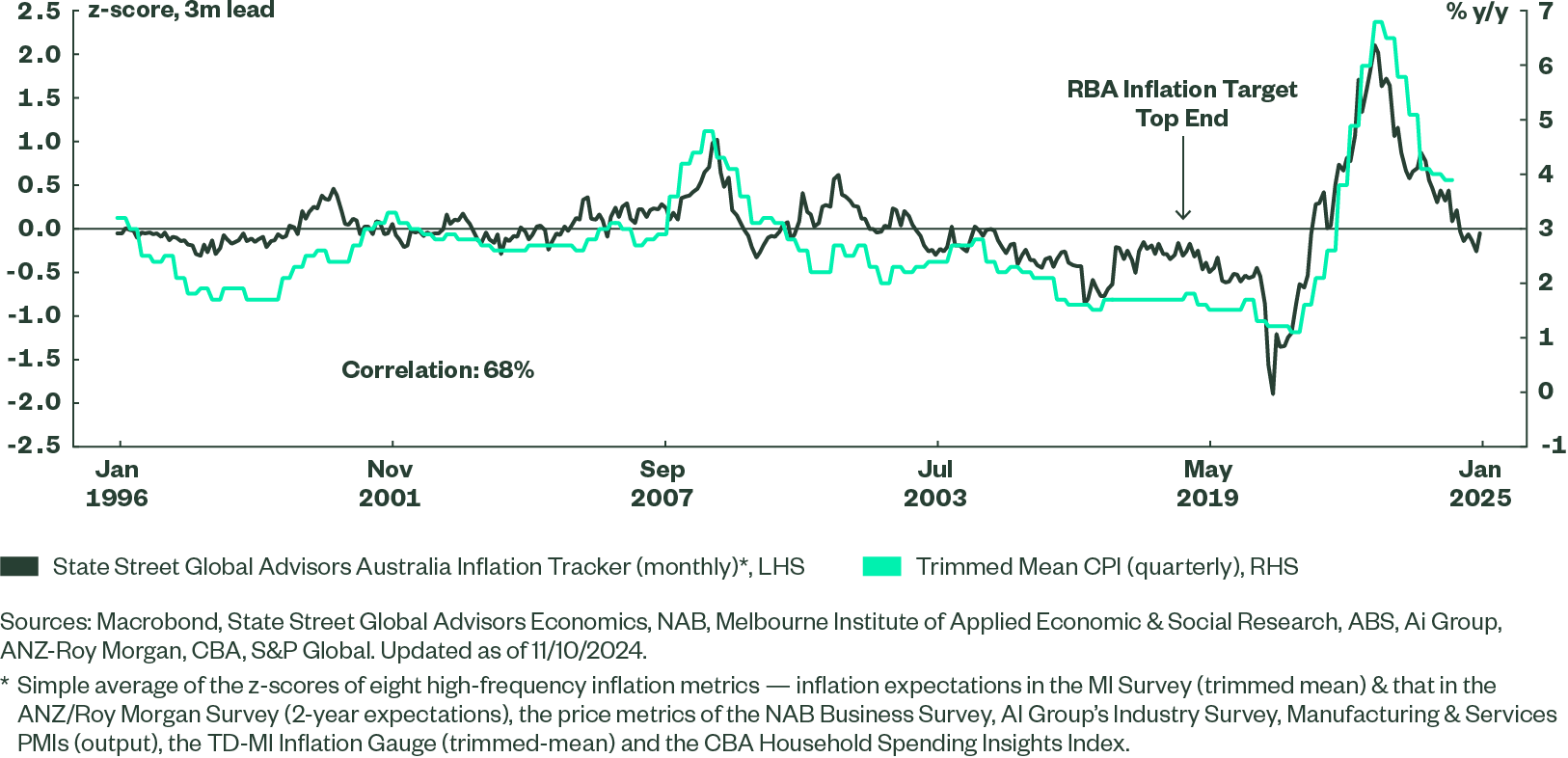

The biggest reason why the RBA should consider rate cuts is clearly and visibly easing inflation. The RBA recently downplayed the fall in headline CPI as it was largely driven by energy subsidies. However, the trimmed-mean CPI eased 40 bps to 3.4% y/y in August, and may continue easing as implied by all timely high-frequency price metrics. Our State Street Global Advisors’ Australia Inflation Tracker leads the headline & RBA’s preferred trimmed-mean CPI and is implying easing core inflation.

Another key reason could be that rental inflation, which has been persistently high since Covid may be easing too, as asking rents in capital cities fell -0.5%, the largest since Covid (source). Most importantly, as highlighted in Table 1, inflation among discretionary goods & services (excluding tobacco) eased to 2.06% in Q2, which means consumption of non-essential items declined markedly, which was echoed by the Governor during the press-conference in September (Monetary Policy Decision | Speeches | RBA “…discretionary expenditure is actually declining”).

Figure 3: Our Tracker Indicates Easing Inflation in Australia

The labour market is generally seen as robust, with monthly job additions printing around 50k for three months, and being led by full-time employment. However, we do see vulnerabilities; 77% of the jobs growth since 2023 have come from just four industries (compared to 52% between 2019-2023). Those industries are driven by the public sector (education & training, healthcare & social assistance, public administration and electricity, gas, water & waste services). This concentration of job additions is quite similar to what has been happening in the US. The difference is that, in Australia, this government sector demand addition added a crucial 0.3 percentage points to GDP growth in Q2 – without which the quarterly growth would have been negative. This higher than usual government demand may have resulted in the government funded sectors having the lowest productivity levels since 2006 (source). We continue to expect a gradual labour market softening over the next 12 months as evidenced by the ANZ-Indeed Job Ads being 28% below their June 2022 peak. This could see unemployment rising beyond the RBA’s forecasted 4.5% in a risk case.

Implications

The RBA has maintained a peak policy rate of 4.35% since November 2023, and we believe a year later will be a good time to recalibrate lower. The scenario has unfavourable market pricing of just 9%, which improves to 40% in December and 47% in February (consensus). With the Fed and global central banks now prioritizing economic growth by lowering rates, it is an opportune time for Australia to lower rates and rebuild its historically higher growth rates. Delaying rate cuts until February might see Australia miss out on growth, and fall off the ‘narrow path’ to a soft landing.

With this gloomy domestic policy and economic outlook persisting we have been advocating that investors diversify their equity portfolios internationally to gain access to the healthier growth prospects available, particularly in the US. These markets have a higher concentration of companies that have the quality factor which allows upside participation while offering some downside protection. Fixed income, both domestic and international, is another asset class that we believe investors should consider. In the current environment, fixed income can provide reasonable yield while benefitting from the coming easing cycle and from any further growth weakness.