Can Australia Survive A Trade War?

Given that a February rate cut by the RBA is consensus now, we explore what may be further ahead for the Australian economy. We see a good chance of an economic recovery due to rate cuts, but the improvement could be challenged by evolving global trade headwinds. It is also plausible that inflation rise as a result of tariff escalations, which may nip a rate cut in the bud – thereby endangering a nascent recovery for the Australian economy. However, our assessment is that a weaker China is the biggest risk on the horizon that could affect GDP growth.

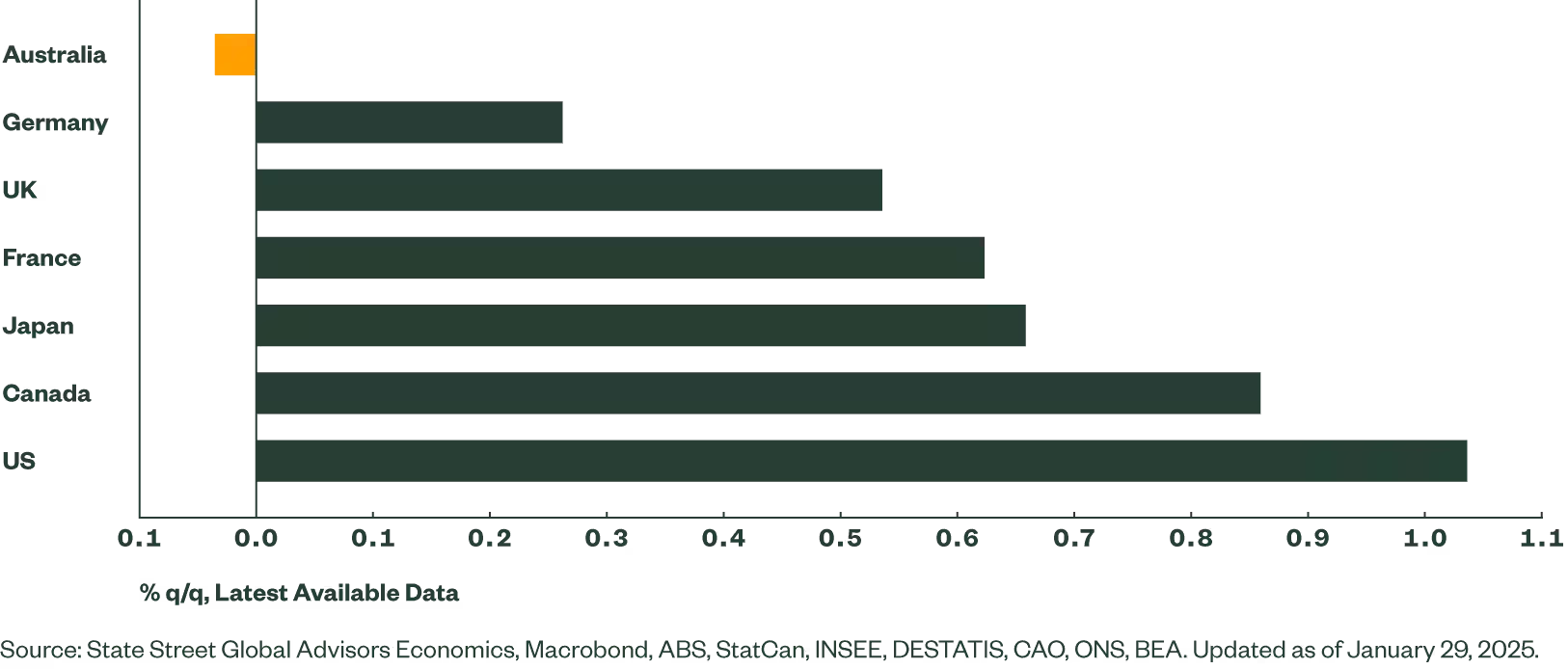

Much of 2024 markets were overtly focussed on Australia’s labour market strength, which consistently surprised to the upside last year. However, we have been arguing that its consumption ranked poorly among advanced economy peers (Figure 1), and that such a strong labour market was unlikely to disrupt the ongoing disinflation, which was proven right after the release of Q4 CPI data.

Figure 1: Australia's Consumption Ranks Poorly Among Peers

This led to a consensus (finally!) for the first rate cut to happen this month (February 2025). For now we expect three cuts this year, taking the cash rate to 3.60% by December. An additional cut may be in store if the Q4 GDP data (to be released on 5 March) show disappointing growth and consumption. However, we think the economy has begun recovering in Q4, albeit slowly.

Tariffs and Australia

The global macroeconomy is on the verge of enormous changes, after President Trump announced that the US would impose 25% tariffs on imports from Mexico, Canada (except oil) and 10% tariff on China. Although the tariffs on Mexico and Canada have since been pushed back by a month, they commenced on China. In response, China has retaliated with a 15% tariff on coal and LNG and a 10% tariff on crude oil and farm equipment and some auto imports.

The path ahead is uncertain but this may be the first salvo in a global trade war as President Trump promised higher tariffs on China and a uniform global tariff for all countries during his campaigning. This then begs the question of the impact on Australia would be from such an action.

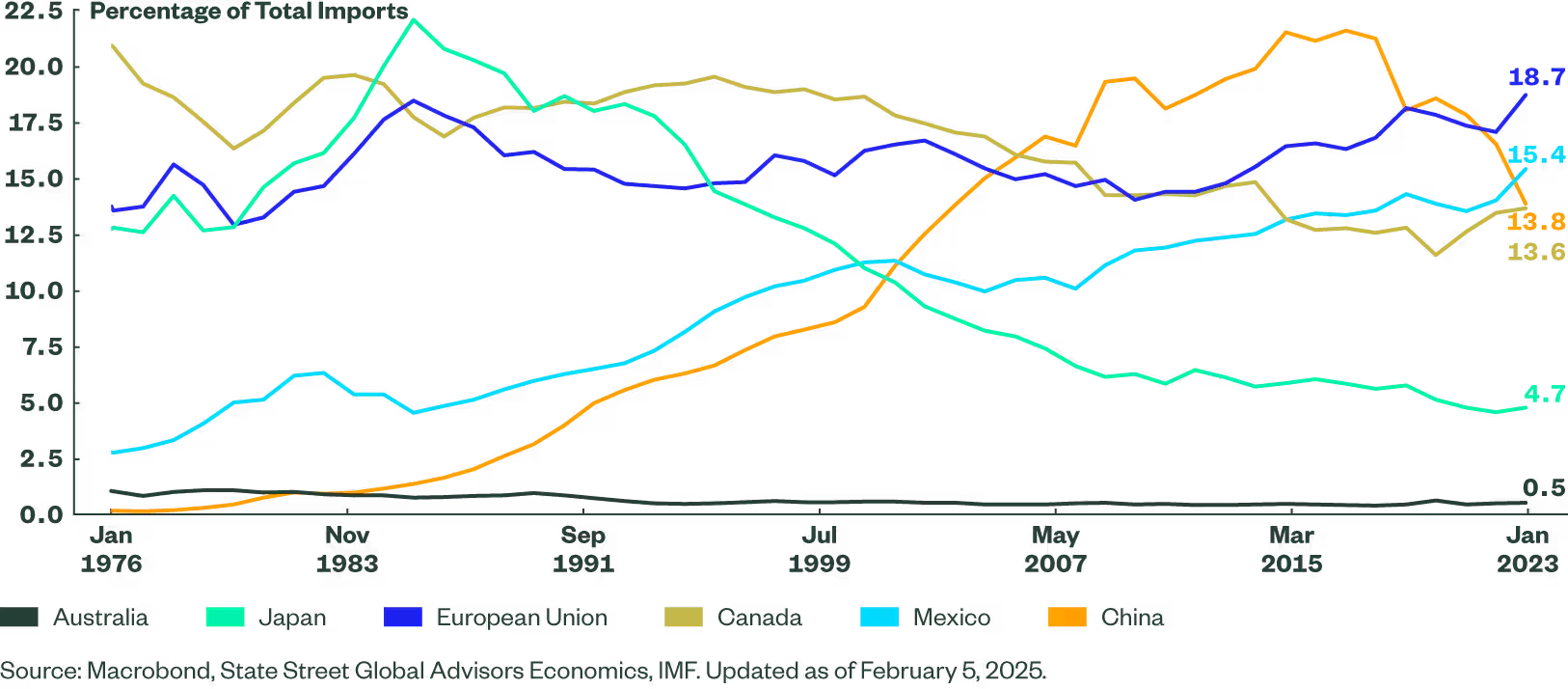

The good news is that US goods imports from Australia add up to just 0.52% of overall US imports in 2023 (Figure 2), an insignificant level compared with the European Union, China, Canada and Mexico. Furthermore, the US has a goods trade surplus of US$17.6 billion, which implies that the likelihood of higher tariffs on Australia may be limited.

Figure 2: Country Share In US Imports

Even if President Trump were to impose a universal tariff on all imports, Australia could secure an exemption, like it did on the steel and aluminium tariffs during his first term. However, Australia may still be affected indirectly through the trade and currency channels. The result of which will be a delayed economic recovery, slightly elevated inflation and limited rate cuts. The adverse risk scenario here would be a sudden steep downturn in global or local growth, in which case inflation may fall materially, bringing in more rate cuts.

So, depending on how the dynamics play out, the impact on Australia may vary. A few scenarios that the RBA modelled when President Trump imposed tariffs during his first term may still be a useful guide. One such example is the extreme scenario where the US imposes a universal 20% tariff rate and all countries except Australia retaliate in same magnitude. Here there is a ‘negative external demand effect’ and Australia’s major trading partners’ GDP would be lower between 3-3.5%. Furthermore, Australia’s financial conditions tighten, lower equity prices reduce household wealth, which eventually leads to lower consumption. GDP level would be lower by 1%, unemployment rate rises and because of this lower demand, inflation would be around 0.2% lower.

Risk to the Baseline Scenario

In our baseline scenario for 2025, we expect a soft-landing in the US, and a turnaround in the Australian economy aided by gradually lower interest rates. A critical and emerging risk is the possibility of slightly higher inflation from stickier services prices and the ongoing strength of the US dollar, that could cause higher import prices.

The US and China account for nearly 35% of overall imports (as of 2023). 40% of Chinese imports were electrical and mechanical machinery and motor vehicles, while majority of the imports form the US were motor vehicles. All of these capital or intermediary goods could have a higher price level in a trade war. Under this risk scenario, Australia’s CPI may average a few notches above our forecast of 2.4% in 2025, but, importantly, will still likely remain in the RBA’s target band. This may delay rate cuts, and the expected economic recovery.

In an adverse scenario, a further slowdown in China’s economic growth may lead to lower demand for Australian exports. That is a worry for Australia given how critical exports to China have been in recent times as an engine of growth.

Opportunity to Mitigate Risks from a Trade War

Trade wars inevitably bring forward negative economic shocks. However, a rare opportunity for Australia exists at least on paper. President Trump reportedly wants Ukraine to export its critical minerals into the US. These are uranium, lithium and titanium. It is already well established that Australia has the world’s largest uranium reserves, is a major lithium producer, and Geoscience Australia classified titanium as ‘high’ on the geological potential (source). It may therefore be a good idea for Australia to pitch itself as a reliable and sustainable supplier to the US for critical mineral needs.

Investment Implications

Despite the risks described above, we expect the narrative of easing inflation and global rate cuts to hold in 2025, and for our projected soft landing to materialise. This landscape extends our favorable outlook for equity markets. US large cap equities retain favoured status in 2025, although there is potential for performance to broaden into small caps, both in the US and emerging markets. An additional benefit for AUD-based investors is that these global allocations could be shielded from some of the expected periodic geopolitical volatility.

Amid central bank rate cuts and easing inflation, the relatively generous government bond yields on offer provide some support for fixed income investors.

However, uncertainty and the potential for higher volatility amid ongoing conflicts and political change means investors should be thoughtful about portfolio construction. We recommend incorporating asset classes like gold aimed at improving diversification that may help mitigate risks.